Historia Linii kolejowej Tajlandia-Birma zwanej "Linią śmierci"

Muzeum w rejonie Hellfire Pass

W 1988 roku w rejonie "Hellfire Pass" rząd Australii wybudował muzeum poświęcone pamięci żołnierzy i pracowników najemnych, którzy zginęli przy budowie linii kolejowej Birma-Tajlandia. Decyzja o budowie podjęta została przez premiera Paula Keatinga w 1994 roku.

Fotografia 236. Budynek główny "Hellfire Pass Memorial Museum".

Fotografia 236. Budynek główny "Hellfire Pass Memorial Museum".

W tym właśnie roku część prochów Edwarda 'Weary' Dunlopa została pochowana w rejonie Hellfire-Pass. W muzeum zgromadzono wiele pozostałości z okresu budowy kolei oraz różnorodnych pamiątek podarowanych przez żołnierzy, którym udało się przeżyć obozy pracy w rejonie "Hellfire Pass".

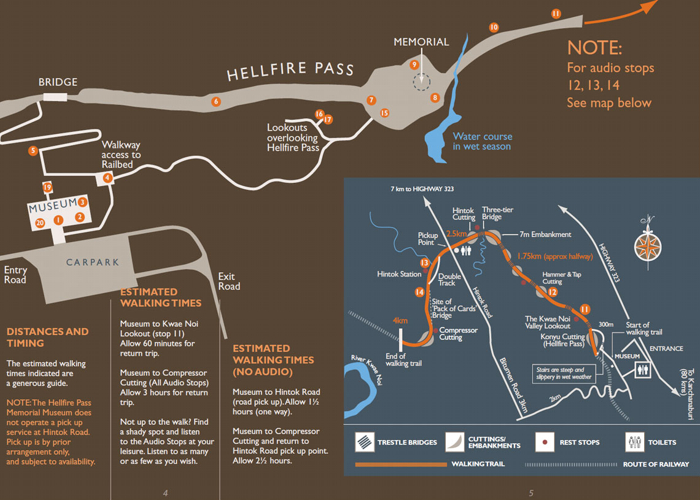

Dzięki zgromadzonym funduszom wraz z budową muzeum udostępniony został 4 kilometrowy fragment szlaku kolejowego od przejścia w skałach zwanego "Konyu Cutting" lub "Hellfire Pass" do przejścia "Compressor Cutting". Na stronach internetowych muzeum udostępniona została wirtualna wycieczka tą trasą w postaci przewodnika audio w języku angielskim, zawierającego opis poszczególnych miejsc wraz z oryginalnymi komentarzami ludzi pracujących w tych miejscach w czasie budowy linii kolejowej. Cały przewodnik wraz z mapą opisującą poszczególne miejsca został umieszczony poniżej. Zapraszamy do jego wysłuchania.

Wycieczka po "Hellfire Pass".

In 1942, at the height of their military power, the Imperial Japanese Army planned to invade India. They needed an overland route to transport reinforcements and supplies. Sir John Carrick, who was an Australian prisoner of war on the railway, explains:

"It was no longer possible for them to go through the Malacca Straits because the American navy was around, so nothing could go through it. That meant that they couldn’t use shipping, and so they had to decide, how could they supply them all together… By mid-1942 they made their decision, and the decision was a decision of desperation, absolute desperation."

The Japanese engineers resurrected a long-abandoned British survey to build a line that linked to the existing Thai and Burmese railway systems. Sir John describes why the British rejected it.

"Well, from Ban Pong to Thanbyuzayat, which was really Bangkok to Rangoon, was about four hundred and fifteen kilometers, but lumpy ones. Up huge hills and dales. And it was so rough a terrain, that to try and build a railway in it was thought to be not only impossible, but if you got it there, who’s going to maintain the permanent way, who’s going to stop the monsoonal periods from wrecking it? Who’s going to stop the bamboo shoots from coming up, the trees from coming up, everything else around the place, so it can’t be done… But it had to be done. When you build a railway line, you build it with your trains coming forward, and you’re just working ahead of it. So that was great, starting from Thanbyuzayat in Rangoon, and starting from Ban Pong on those flat plains.

But they didn’t only do that. They decided to march prisoners of war into the jungle, along the whole track, along the whole way that was going to be. And in absolutely primeval forests, set them to make their living space, and to start clearing and to building permanent ways. That meant that the problem of getting elementary supplies, was almost impossible."

With little more than the most primitive tools, some dynamite, and the blood and sweat of Allied prisoners of war and Asian labourers, work began in Thanbyuzayat in Burma on the 1st of October 1942. Almost simultaneously construction began on the other end of the line at Ban Pong, Thailand.

The track wound along 415 kilometers, spanning rivers and snaking through mountainous terrain. Japanese engineers estimated that the railway involved constructing 4 million cubic meters of earthworks, shifting 3 million cubic meters of rock, and constructing 14 kilometers of bridges.

A job that the British had once estimated would take six years took fifteen months. The prisoners, along with the Asian labourers, covered an average of 890 meters of track per day. The railway joined at Konkoita - a place now flooded by the Vachiralongkorn Dam.

Fotografia 237. Rejon "Hellfire Pass" w raz z zaznaczonym budynkiem muzeum i szklakiem kolejowym. Poszczególne punkty wskazują miejsca omawiane w przewodniku audio.

Fotografia 237. Rejon "Hellfire Pass" w raz z zaznaczonym budynkiem muzeum i szklakiem kolejowym. Poszczególne punkty wskazują miejsca omawiane w przewodniku audio.

Część 2. Początek.

After you’ve read the visitor’s information sign, and you’ve checked your water and sunscreen supplies, we can begin our descent into Hellfire Pass. Got your hat. You can listen now as you make your way towards stop 5.

Men who worked here knew it as the Konyu cutting. A hill had to be cut through to make way for trains to pass. The tools were primitive and the men seriously malnourished and diseased. The heat, the cold, and the monsoon rains exacerbated the oppressive violence of the forced labour. Men cut through the mountain with hammers and man-held drills. This work became known as hammer and tap.

Cutting through the rock was laborious, tedious and slow. Hellfire Pass became a bottleneck in the system. The Japanese engineers began to apply maximum pressure. Teams were forced to work around the clock. On the night shift, bamboo torches and smoky fires provided light. It was noisy. Incessant hammering was consistently punctuated with the sounds of engineers and guards screaming, Speedo! Speedo! Speedo!

Jack Chalker wrote, “The place earned the title of Hellfire Pass, for it looked, and was, like a living image of hell itself”.

As we make our way down the walkway, take time to consider the one and only resource available to the prisoners of war – tall, plentiful clumps of bamboo. As you can see, it grows everywhere.

Bamboo was used for almost everything.

It was a devil to cut, but pliable and soft to work. Prisoners of war initially constructed an intricate system of bamboo plumbing. They used bamboo containers to hold clean water. There were bamboo beds, and bamboo bedpans. Bamboo stretchers, bamboo splints, and bamboo stands to hold saline drips. They built bamboo bridges using bamboo scaffolding. There were no nails or wire, just jungle fibres to hold it together. They leaned on bamboo walking sticks, and hung what remained of their clothing on bamboo washing lines. They slept in bamboo huts with bamboo floors. They used bamboo poles to carry rock, and often ate off bamboo plates. There were bamboo fires for cooking, heating, lighting and for funeral pyres. The ashes of every man cremated were kept in a separate bamboo container, cut straight from the bamboo.

Bill Dunn remembers:

"We couldn’t have survived without bamboo. Everything we did was with bamboo. We existed with bamboo. There wasn’t any substitute really, for it… (13:45) In one of the base camps, we had the bamboo morgue. It was made of bamboo and just attap morgue. And this strange little fellow from one of the units, this night it was his duty to carry the corpses over and lay them in the morgue. He carried one over, and shortly after he carried another one over, and just as he laid him down, the wind came out of the other chap’s lungs – he went straight through the wall – he didn’t go through the door – and the hole was there in the morning, he went straight through that bamboo wall on the morgue."

For all the grand things bamboo could do, it had a sinister side that made the men wary. Clearing impenetrable thickets of bamboo was one of the toughest jobs. The iron-hard spikes sliced through flesh often resulting in painful and even deadly tropical ulcers. The clumps were full of wasps’ nests and every other kind of biting insect. And, then of course, no one escaped the whipping from a guard’s bamboo rod.

These stairs wind down to the actual cutting, to the place where the railway track was set to pass through the mountain. From there, it’s quite a way to our next stop, but there is much to reflect upon. Along the way you will see information panels, original sleepers, tracks and official as well as spontaneous memorials. Just imagine. The entire path was carved out of the mountain by hand, rock by rock.

Here we have a broken drill bit still embedded in the rock:

"You can see the drill marks here. You can see them going vertical. You can see them going horizontal. You can see them going oblong, at obtuse angles. Anywhere they could get their drill in to make a bite. The majority of this work was done by hammer and tap. A sledge hammer, a still drill. One full blow, and it had to be a full blow because they couldn’t get the drill to turn. And they had to put water in to soften it when they were drilling down. And they had to be careful not to dampen the end of the drill where they were drilling, because otherwise the powder from the cordite and from the dynamite they were putting in wouldn’t allow detonation."

Fotografia 238. Złamane wiertło znajdujące się na mapie w punkcie nr 6.

Fotografia 238. Złamane wiertło znajdujące się na mapie w punkcie nr 6.

Towards the end of this massive excavation, as the Imperial Japanese Army became increasingly desperate for the railway’s completion, they sent in compressor drills to help with the cutting. Bill Dunn remembers it well:

"Towards the end of K-3, they brought in an old compressor. And the jolly thing had a great hole in the middle of the radiator, which meant that we had to keep pouring water in the radiator all the time to keep it working. And I was involved in the water party this particular night, and we had to walk back to where the camp area, the creek ran through the camp area for our water supply, and we were carrying the tins of water and pouring them in that kept the compressor going all the time like that. And we were half-way back that night, and this chappie from Wagga and myself had a big four gallon tin on a bamboo pole between us, and there was a rustle in the bamboo. And Geoff said “Panther!” and he came to the on-guard position with the bamboo pole that had the water, and it turned out it was an elephant rustling the bamboo with his trunk, so we had to go back and re-fill up."

Every year a dawn ceremony is held on Australia’s Anzac Day.

Fotografia 239. Ślad w skale po wiertle w rejonie przejścia "Hellfire Pass".

Fotografia 239. Ślad w skale po wiertle w rejonie przejścia "Hellfire Pass".

Bill Slape describes it:

"Anzac Day starts on the 25th April, at two in the morning. The first guests arrive around about three thirty. When people walk into Hellfire Pass the pass is lit up, very serene. There are about 25 petrol lanterns which they made sixty years ago as well; we’ve tried to replicate that. Normal wax candles are handed to each individual walking down into the pass, and that acts as a lantern, and also as a lamp when they’re reading their service books. At the end of the pass there is a memorial where everyone gathers. Speeches are given by the ambassadors, of Australia and New Zealand, and also the POWs. We’ve made a stand for schoolchildren from all nations. As you enter the pass on the left hand side on the top of the hill there is a bagpipe player, and on the right hand side is a bugler."

"Now they will not be seen by the masses until they actually play their part. The ceremony lasts for about a half an hour, and dawn does rise in that period, and everyone mixes in with the POWs and the POWs just love talking to the younger generation… Hellfire Pass is a unique place, for myself and for other people, there’s always a sense of – there’s a sense of feeling. It’s a warm feeling, there’s a sense that there’s a presence, like a POW presence. I can’t explain it, other people can’t explain it either, but they feel it. You feel something here."

In May 1943 cholera swept through the railway with a hideous ferocity. Bill Haskell describes the disease:

"Now, what cholera does, it affects the fluid system of the body, and you’re exuding a whitish fluid… you’re defecating and vomiting a whitish fluid which rapidly, I mean really rapidly dehydrates you. Your best friend you would not recognise an hour or two into a cholera attack, because it just takes all the fluid from the body and they’ve got little wrinkles in the skin, and the eyes recede, and its just awful. Its incredible it makes just a little hulk out of a strapping man, in a matter of hours. Then, because the fluid leaves the body, it takes the body salts, so alongside of that, because you’ve lost your body salts, all your muscles contort and cramp. And its just hideous, the stomach and legs and arms, are just contorted in cramp."

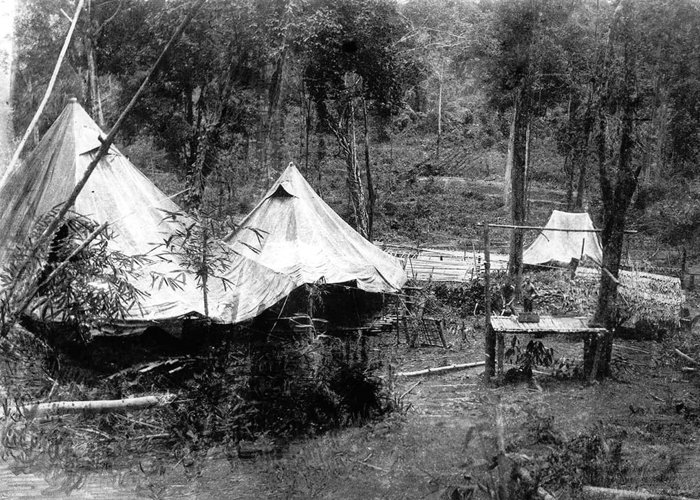

Fotografia 240. Odizolowana część obozu "Lower Sonkurai" zwana "Cholera Hill". Tu w namiotach przetrzymywani byli chorzy na cholerę. W środku zdjęcia widoczny prowizoryczny bambusowy stół przeznaczony do amputacji kończyn.

Fotografia 240. Odizolowana część obozu "Lower Sonkurai" zwana "Cholera Hill". Tu w namiotach przetrzymywani byli chorzy na cholerę. W środku zdjęcia widoczny prowizoryczny bambusowy stół przeznaczony do amputacji kończyn.

Doctors were forced to come up with ways to hydrate cholera victims. Dr Rowley Richards recalls:

"The important thing was to get fluid into their veins, and if they, the needles that we had were not suitable, there were always people in the camp that could do things for us. And they would knock off pieces of copper tubing out of the Jap trucks or whatever. And they would make out of that thin tubing, canulas to be able to put into the veins, so that we could get the liquid in."

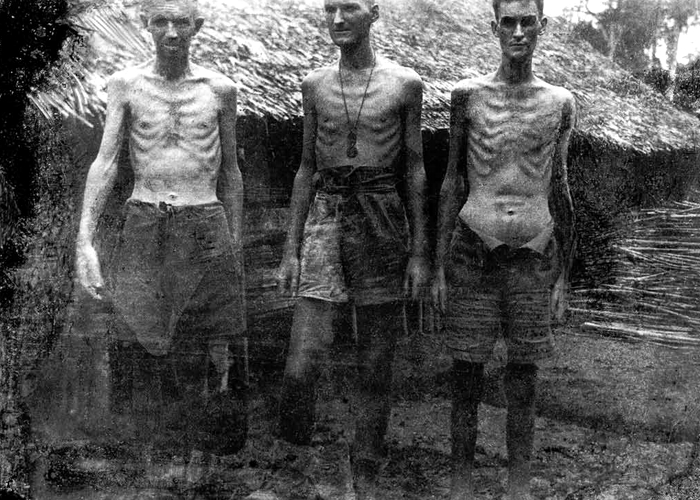

Fotografia 241. Mieszkańcy odizolowanej część obozu 'Lower Sonkurai' zwanej 'Cholera Hill' przeznaczonej dla żołnierzy zarażonych cholerą.

Fotografia 241. Mieszkańcy odizolowanej część obozu 'Lower Sonkurai' zwanej 'Cholera Hill' przeznaczonej dla żołnierzy zarażonych cholerą.

Stan Arneil’s diary entries chart the daily horror:

“18th of May: one died last night from cholera … 20th of May… four new cholera cases … 21st of May … two more deaths from cholera … 22nd of May … one more cholera death last night … 23rd of May … Four more cholera suspects this morning. Every day the tally mounted. Three on the 25th, five on the 26th, and 12 on the 27th. Bodies were cremated on funeral pyres that burned all day through the deadly months of May and June."

Of all the groups working on the railway, the Australians managed to best contain the dreaded, feared cholera. They instituted the strictest hygiene possible in the circumstances. No man ate until he’d dipped his dixie in boiled water. Other nationalities took up these methods.

This plaque immortalizes Weary Dunlop’s truly remarkable leadership and his fastidious care for the men in Dunlop Force. Every day Japanese engineers demanded their daily quota of men required to work, and each day doctors were forced to decide if one man’s malaria was more serious than another’s maggot-infested foot ulcer. Or perhaps if this case of beriberi was more life threatening than another’s dengue fever.

Fotografia 242. Pamiątkowa tablica poświęcona Edwardowi Dunlopowi. Na mapie znajduje się w punkcie nr 7.

Fotografia 242. Pamiątkowa tablica poświęcona Edwardowi Dunlopowi. Na mapie znajduje się w punkcie nr 7.

By every account Weary Dunlop was a most extraordinary man. Dr Lloyd Cahill remembers their meeting:

"The only time I met the great man from Melbourne, he was talking to me and a little Jap came along and screamed something at him, and he took no notice of him at all. And the Jap went away and he came back with something or other, and started to perform, and he still took no notice. And eventually he came down and started to beat him with a bamboo around his legs, and Weary just didn’t take any notice of him at all, and eventually he just got fed up and walked away. So he was a very impressive fellow."

There were dozens of Australian, British, Dutch and also American doctors on the railway. Each morning they’d do god almighty battle for the prisoners they believed too sick to work. As Bill Dunn explains, the measure of a man’s ability to work was sometimes determined by the amount of blood in his stools.

"The selection of the working parties, they didn’t tolerate sickness. So the one doctor we had there, Dr Parker, had to try and protect the heavy sick in some way, but it was most difficult. The guards who had no medical knowledge naturally, when we were picking the working parties of a morning, at daybreak, we’d all have to squat and do a stool on the ground. And these guards would come along and if it was 50% blood, you were fit enough to go to work – 80% they might give you the day off, but that was all. So that’s how the working parties were kept up to strength."

Doctors were forced to perform major medical procedures with the most rudimentary medical equipment, and virtually no medicine.

Dr Rowley Richards explains:

"Well, it was a question, obviously, of innovation all the time. For instances, bandages – we tore up sheets as they became unserviceable, or mosquito nets, or blankets, or whatever, into strips, and boiled them, and reboiled them, and boiled them again. To try and relieve some of the symptoms of the dysentery for instance, I used to get the sick men, all the light duty men, to make charcoal. The charcoal was supposed to relieve their symptoms of belly-ache and whatever. Psychologically I think it helped them."

The heroic efforts of the doctors were supplemented by the equally compassionate care of untrained orderlies. Sir John Carrick recalls their work with the dying:

"They were holding the patients, they were giving love, they were giving real affection. And death in itself, was not a clinical aseptic kind of situation at all, it was there. And accepted. It was ugly, but it was accepted."

Every single man that spent time constructing the Burma-Thailand railway experienced frequent attacks of diarrhea and battled bout after bout of malaria, as well as other diseases.

Bill Dunn says:

"It was a funny thing, I had 43 attacks of malaria… when you say attacks, they were relapses really, and I only ever went delirious twice. But I always used to say the first thing I want to do when I get out of here is get an attack of malaria so I can have sheets, and a pillow, and blankets. And sure enough I did. I was in Bangkok Hospital the first week. The relief was lovely."

Weary Dunlop has become the best-known of the doctors, but he was but one of many very impressive medical men. Names like Kevin Fagan and Bruce Hunt are talked of in the same loving breath. The doctors on the Death Railway are all regarded as heroic and saintly men. They sacrificed, suffered, and stitched together the body and soul of their troops who worked, starved, and died constructing the ill-fated rail link from Thailand to Burma.

Look back down the length of the cut… Then take a moment to consider the logistics of drilling through this solid rock hill, wide enough for trains to pass through. This super-human feat was accomplished amidst unrelenting human horror. Every millimetre was carted away by hand. Work was enforced by Japanese and Korean guards, but the details were organized and orchestrated by the Japanese engineers.

Fotografia 243. Pamiątkowy pomnik stojący w połowie długości przejscia w skałach zwanego "Hellfire Pass".

Fotografia 243. Pamiątkowy pomnik stojący w połowie długości przejscia w skałach zwanego "Hellfire Pass".

There was a strict chain of command, with the engineers at the top of the hierarchy, and the Korean guards just one rung above the prisoners. Each rank was free to bash the ones below. Savage beatings were inflicted on the weakened and disease-ravaged prisoners. No man was allowed to stop work to assist his mate. Men with dysentery or diarrhea had to wait for permission before making their urgent dash into the bush. It’s estimated that about 70 men who worked on this section alone, were sadistically murdered by the guards – others were beaten so severely they were forced to spend months in hospital.

Every guard was given a nickname. Fatso, Boofhead, Poxy Paws, Dr Death and The Maggot. Bill Dunn explains:

"One in particular we had, by the name of Battle Gong, and Battle Gong – we named him because he’d lost three fingers fighting in China – and he carried a wrench, maybe two feet long. And he belted you with his wrench. He was the worst. We had another one who we called the Silent Basher. Now we had to file past the Silent Basher every morning going to work, and he’d give you a left and right to the jaw. And at night, maybe ten o’clock, eleven o’clock at night, coming back out of the cutting, he was down there and you got another left and right to the jaw. But he never spoke for the three months we were there – he never uttered one word. And that’s how the name Silent Basher came by."

Fotografia 244. Przejście w skałach zwane "Hammer and Tap Cutting".

Fotografia 244. Przejście w skałach zwane "Hammer and Tap Cutting".

Prisoners on the railway were organized according to nationality. From the beginning of captivity they retained their existing rank, command structures, and discipline. Allied officers answered to the Japanese, and were responsible for administering their camps and taking care of their men. Some believe the Australian troops survived more successfully than their British and Dutch counterparts, because their superiors were not so burdened by attitudes of class and race. But even the most recalcitrant soldiers realized that their very survival depended on this discipline.

Asian workers recruited or forced to work on the railway lacked this internal cohesion. Many arrived with wives and children. They had no sanitation, very few medical facilities, and no real leadership. They were kept working long after their three-month contracts expired. Their lot was even worse than that of the prisoners. They were especially hard hit by cholera, the most feared disease of all. Most of those who died on the railway were Asians

No one’s entirely sure of just how many, but it is estimated that up to 90,000 died.

Captain Lloyd Cahill, an Australian doctor, recalls a horrifying scene in one of the Asian camps:

"After we’d got the first lot, the first attack of cholera cleared up… The nips then got the great idea, various Indians and Malays, the whole lot, they were bringing them up to work on it, but they ran into cholera, and cholera everywhere. So here we were lobbed back in the cholera. After about three days, they let me go in to see what was going on there. So I went down there and it really was dreadful, it absolutely was dreadful. The poor mothers, a lot of them were there, dead parents, with the babies looking around for a feed, trying to suckle, something I’ve never seen before. And the Japs would say, no, no, you couldn’t do anything at all with it."

This monument was erected by the Australian Department of Veteran Affairs to honour all the men who died here.

This is not the most comfortable place, but let’s sit here for a while anyway. Close your eyes for moment. Imagine heat and humidity, hunger and disease, rain and wind, bashings and pain. Although all the troops had grown up in the Depression, and many had been used to the rumblings of an empty belly, hunger on the railway was a permanently nagging, gnawing state of being.

John Varley says:

"Food… lack of it…. It was a perpetual worry, or you know, you always had an empty stomach, and you were wondering where the next, what the next meal was going to be like. And if you could scrounge something else, or what else you could eat, sort of thing. The whole world seemed to revolve around two things – the fear of the Japanese and their ill-treatment, and what food you were going to eat."

The inherent problem of supply was further aggravated by the Monsoons. Impassable roads and flooding rivers so slowed the transportation that when the food finally arrived it was rotten and in various stages of decomposition. There were infinitely more maggots than there was meat. The rains coincided with the Speedo period. Men were forced to work longer and harder on increasingly diminishing rations. At most, they were getting a quarter of the nourishment required to keep alive, let alone be working.

They were rationed to three small dollops of rice which was often watery-boiled to form a porridge-like substance called pap. The pap was occasionally supplemented with a broth made from a scrawny old yak. One carcass shared amongst 800 men.

Dr Lloyd Cahill still has an affection for rice, but not surprisingly, little else from those dark days takes his fancy:

Well, there was no food – all they got was a bit of rice, boiled rice twice a day, and you could get by on that. In fact, most prisoners of war like rice now – I can eat rice three times a day, its quite extraordinary. But the food was dreadful. The worst I saw was to give rice with a bit of so called meat in it. It was sun-dried bird’s tongues. They’d get their tongues and sun-dry them like with the tomatoes, and give you that to put on your rice.

Bluey Butterworth describes the dried fish:

"In the store where they stored it, you’d swear blind it was going to move off – it was rotten, maggots, you name it, it was riddled. But it brought that flavour to the rice. And then of course we had the duck egg. And duck eggs tasted of fish. The duck eggs used to be black, where the sun had been catching them, you’d open them up there, and the smell of the fish and the taste of the fish in the duck egg, just did something for the rice. So we thoroughly enjoyed the maggots, and the rat droppings, and all those."

This grossly deficient diet coupled with a lack of clean water led to serious disease. Almost everyone suffered from diarrhea. There was pellagra, avitaminosis, dysentery; and beriberi sometimes so bad that men had to cradle their enlarged testicles just to move.

And yet amidst all this misery they found a way to laugh at their predicament. Jack Chalker wrote about the daily competition that took place in the dysentery hut where “Skeletal inmates instituted daily sweepstakes on individual scores reached in motions per day, and the man who reached the highest score without cheating won a cigarette from the pool. Some of the winning scores, which were strictly accounted, reached 60 or 70 for a 24-hour period.”

Smokers put food before cigarettes. Parkin went further. He declared: “We have all decided that Sex is out and Hunger is king.”

We’re now standing on the old railway track. There was once a trestle bridge right here. It was close to 200 meters long. Let’s start walking… A few steps down, just over to the left, you will see the cement footings with the bamboo indicators. Over on the right, a little further along you’ll see big holes drilled into rock. These held the bridge’s support struts. Some of the original teak sleepers are still in place.

Look straight ahead, along the path you’ll see an original dry-stone wall. It’s built from the rock that once formed the hill through which Hellfire Pass was cut.

Feel the discomfort of the stones underfoot as we walk towards the Kwae Noi Lookout. Imagine doing this walk hour after hour. Through searing heat or bucketing rain. By the light of day, or the dark of night. Carrying rocks, stones or heavy teak sleepers on swollen ulcerated feet. Up and down. Back and forth. Ray Parkin talks of it as “a regular, funeral tramp, of corpse-like monotony.” He goes on to explain that “The simple fact of picking up the stretcher, and the strain of weight on one’s arms, clogged the mind to a sodden mass like the earth itself. No thought in the mind save … Drudgery … Oppression … At such times we are silent as ants. Often, for the life of me, I could not tell you what my thoughts are and I am conscious of nothing, save of my feet jolting up from the ground.”

Most men trod this path barefooted. Boots were a rare commodity. Most had rotted or worn out. Cliff Moss was one of the lucky ones:

I had boots for most of the time we were in Thailand – I was very fortunate in that respect – I had a good pair of boots when we got there and we were in Tarsao, I was in there for a while when I was wandering through some tall grass about fifty yards from the hut and I found a pair of boots. Now I presume somebody had pinched these things and planted them there and couldn’t find them again, or wasn’t going to. And they were my size. So I was very, very fortunate.

Whatever clothing the men arrived in soon wore to shreds or rotted. Eventually the Japanese issued cotton lap-laps - a type of G-string, which they referred to as “Jap-happies”. They worked in these by day, and saved whatever was left of their clothing to keep them warm at night.

This is a good place to rest… Look carefully into the far distance. Do you see the shape of a white water tower? The little white speck, just over to the left? That’s where the Japanese kept their supplies. Beyond the mountain ranges, 47 kilometers away is Burma.

This is quite lovely, don’t you think? It’s a still kind of beauty, and it offered many a miserable man solace during his period as a prisoner.

In his diary entry dated the 4th of April 1943, Weary Dunlop wrote:

“The morning and evening sometimes positively hurt with their beauty, especially the lovely quarter hour before dawn when the whole sky is aglow with brilliant crimson bands showing through the clearly etched foliage in a brilliant atmosphere and the softest of pale blue. Vividness and colours everywhere.”

Tom Uren vowed to return to this beauty under different circumstances:

If I can say this about the forests, on the mountain tops they used to have a place where they had a forge, where they used to temper the steel drills. And I’d walk into this and sit on this 44 gallon drum and put my feet into the water. And I’d look out, and I’d look into the forests and winding river, and I’d just think what a paradise, thinking, I must go back after the war to see it, because I was so impressed with the forests. But when I went back in ’87, you know there wasn’t one tree left. Not one teak tree left – plenty of bamboo – but not one stick of timber. They had just raped that completely.

Ray Parkin believed that the sheer Nature around him could help make up for what he lacked in food and comfort. He wrote “There is much to admire in the country. In spite of our situation, there is something here which is giving my heart a lift: perhaps it is the much good against which to contrast our little evil, giving a sense of proportion.”

Parkin was captivated by the jungle flowers. He painted hooded lilies and clumps of orchids. He marveled at the many varieties of butterflies floating in long, colourful chains, and wrote of the indigo mountains, and the “graceful flights of geese”. While pondering the smoky mists of dusk, he asks “Will we be the ghosts to haunt this jungle one day?”

We’ll carry on our journey towards stop 12 the Hammer + Tap cutting. Look at your map and see if you want to join us there. If not, you can always listen to the next three stops as you walk back towards Hellfire Pass.

Not a single machine was used in this cutting. It was straight hammer + tap. But all around the resources of the jungle were exploited. Heavy teak and other hardwood trees were felled to make railway sleepers and bridge pylons. They had to be cut and transported. Elephants would sometimes be used for lifting, but mostly the logs and sleepers were carried by sick and emaciated prisoners.

Eric Wilson remembers:

"One camp, we got there before the engineers were ready for their part of the work, so they had us on cross-cut saws, felling trees, which were going to be used subsequently for the uprights for the bridges. In spite of the Japs insisting we keep on cutting till the tree’s ready to fall, we tended to step aside a bit before that, and the trees didn’t always fall where they wanted them to. We thought this was great fun until, at some stage, one of our fellows said to the Japanese NCO “When are the elephants coming to haul these trunks down”. “Elephants, no,” he said, “British”. But we were all British as far as the nips were concerned. So we were told no, no elephants."

Ray Parkin describes tree-felling a steep rocky hillside on the Hintok Road: “The trees grew out of the rocks and their roots seemed to have split them. They were teak, mahogany, coral, acacia, kapok, and others I had no idea of. There were plenty of traps. We started at the bottom to avoid crushing anybody below and to avoid a tangle: the vines in the branches often will not let the trees fall.

Then came the tricky part: picking the right ones to free, and dodging quickly when they came; for they never fell true, and brought down tops from nowhere. When they hit they bounded downhill like something alive.”

Roydon Cornford was in a group that laid rails:

"We were in the line-laying gang, so the other camps ahead of us, they were the ones doing all the clearing, and all the bank work, building the banks up so that we could lay the line. We’d lay so many lengths of line, then we’d go back, then we’d have to load metal to put in between the railway lines. Then we’d have to bring that up, then they’d bring up more trains, more lines and more sleepers. And then we were dying off that quick, at first we had to carry the sleepers and all, but in the finish they had natives carrying the sleepers – we still had to drill the holes and gauge the line and all that, but in the finish the natives carried the sleepers, because there wasn’t enough of us alive."

Dr Lloyd Cahill found other uses for the newly laid track:

I got fed up with living in the mud, so I climbed up on the top of railway lines and you could get a reasonable rest there – you’d get your hip in between two, somewhere to put your hip on. And one night I heard a train coming at about ten o’clock, through the jungle. And then it came and all these little steel trucks like they brought us up in, they were there, and the doors opened, and out popped a whole lot of girls, dressed like nurses. And of course this was the travelling brothel that arrived up there.

The women, who arrived on that late-night train, were known as comfort women, and they were prisoners in their own right.

Hintok Station was located 5 kilometers north of here. Conditions of camps along the track ranged from abysmal to horrific. Generally, the closer to the middle of the railway, the more shocking the camp. Hintok was one of the worst.

As each section of the railway was completed, the prisoners of war and labourers were moved on to the next camp, often leaving behind their dying and their dead. Camps were usually made in jungle clearings on the side of the track, and were roughly 20 kilometers apart. Men slept in huts constructed from bamboo bound together with jungle fibres and palm fronds. They had attap roofs – which is a type of thatch made from overlapping palm leaves. They slept on bamboo-slatted sleeping platforms. Ray Parkin describes them as “rougher than anything man has slept on since the Neolithic age.”

By the time the men reached a new camp, the existing huts were sometimes so decrepit that they chose to sleep on the ground. Roydon Cornford, who later also survived the sinking of the Japanese transport ship Rakuyo Maru in 1944, says:

"… if you didn’t have a couple of old rice bags or something, you were just laying on these slats. I’ve met a few people who slept on the ground – they caught pleurisy – and then the next thing they had pneumonia and died, from sleeping on the ground. …But I’ll admit, I did have a couple of corn bags and I made meself a bit of a bunk with two poles all through the camp. And you had bugs and bed lice all the time – you could pick the bed lice off yourself the next day."

Then there were problems of fresh water and personal hygiene. In the early days Australian prisoners of war were renowned - and envied - for their inventive bamboo plumbing systems. They built showers, elaborate urinals and toilet pits covered with bamboo seats. But by the time the monsoon rains came and Speedo work principles were in operation, you could smell the stench of any camp from 200 meters down the jungle path. Flies swarmed thickly around latrines. Men with amoebic dysentery and chronic diarrhea could not find their way in the dark. Rain flooded toilets to overflowing. Raw sewage swirled around the boggy mud.

Hintok Mountain Camp was an Australian camp, although just over on the other side of the creek were British prisoners. It was a place where Weary Dunlop’s superior leadership skills were strongly felt. Tom Uren remembers:

"Most of our time was at Hintok Mountain Camp, and Weary had set down a kind of principle that you would go and get – he was able to convince the officers to put the bulk of their money into a central fund. Because the Japs were paying both our officers and the medical orderlies an allowance as a sham to keep the principles of the Geneva convention. And the minute we had to work, they got more wages and the bulk of their money went into the central fund. And Weary, with that money, would send people out into the jungle to trade with the Chinese and Thai traders. They’d get drugs and food for our sick and our needy. In our camp it was the strong looked out for the weak, the young looking after the not so young, and the fitter looking after the sick. This was the collective spirit. Now that’s saying something, but really this collective spirit under Weary, and I’ll never forget it."

Hintok was a stop on the track for those marching through. Bill Haskell describes the way groups were kept separate:

"You never met up with any group working. The idea was, they had so many camps interspersed along the whole stretch of the railway. And you never got to talk to people from other groups. You were just ostracized in that regard, and even though they were only probably a mile or two away, you never ever seemed to get to talk to them. Excepting when the various forces like F-Force, when they came up the line they came through our camp, and we spoke to them at different times."

The Australians operating out of here were assigned some of the most backbreaking, treacherous work on the railway. Deep cuttings were forged out of hard sandstone, and steep stone embankments had to be built over rocky terrain.

Down on the left is where the notorious “Pack of Cards” bridge stood. It was a three-tier trestle bridge which attempted to circumnavigate the curve of the mountain. It was 400 meters long and stood 27 meters high. It was built with whatever wood the jungle had to offer – from the hardest teak to the softest kapok. Just so long as the log was the right length.

No one was terribly sure of how to go about building a big bridge on a curved site. Not even the Japanese engineers knew exactly how to go about it. Ray Parkin, who worked on the construction wrote, “The Japs we are with have no idea of rigging. To them the breaking strain of a rope or wire is only when it breaks. After a few hair-raising accidents, a couple of the sailors amongst us said we would show them. This has saved them breaking so much gear, and it has also saved our lives and limbs.”

Bill Haskell also worked on the bridge:

"I worked on what they called the seven metre embankment, and that was just cruelty personified… to put that embankment up you had to grist the sand from the surrounding country which was just all rock, and there were pockets of sand across the rock, it all had to be garnered out and carried in baskets, or what they call a tanker, which was a rice sack between two bamboo poles.

And all the time the embankment was rising you had guards there belting all along the track, and rain, and it was glug… you’d fall over and bury your face in the dirt. It was just incredible the cruelty that went on, and the constant yabber. And that seven metre bank is, I don’t know, probably about 400 yards long, and it has a curve; it cost so much in lives, not on the job, but men just gave it their everything there, because to get there we had to walk out from Hintok Camp, which in the darkness is a terrible thing.

We were barefooted, we came from G… but most of our blokes were barefooted, and it was a very gruelling task. From there, adjoining the seven metre bank you have the Three Tier Bridge, which quite often is called the Pack of Cards bridge. It was probably in the order of about 80 or 90 feet high, three tiers, the abutments on the northern end are still there, you can see the three abutments.

It was built with timber cut in the jungle, dragged to the site, and erected on the site. It was controlled by a brutal sergeant, a sergeant engineer who everybody referred to as Billy the Bastard, because he would be working up on the bridge and people down below, he would throw anything at them, for no reason at all, just because he felt he was a little upset on the day, or things weren’t going his way. He would just let drive with anything – he was the essence of cruelty to the men. However, that bridge was built from Hintok Camp where I was – we used to walk there.

we all worked on the Pack of Cards, and the reason it was put through was that the train was waiting back there at Konyu and it had to be done quickly, and they brought in a huge number of Tamils … There was, in the height of the monsoon season, there was a real current running down, and of course the footing kept getting knocked and then it would collapse…."

From up here you get the full picture of the cutting that became known as Hellfire Pass. It’s 600 meters long and 25 meters deep at its highest point. When Bluey Butterworth saw the jungle-covered hill, he honestly believed there was no way a railway track could pass through.

"When I first went there, and saw the track, just all the clearance of bamboos, I thought these bastards will never build this. I thought cripes, the way we were, and there was no machinery then, it was all physical, all manual. I couldn’t see it."

But they did. Using only picks and shovels, eight to ten-pound hammers and sticks of gelignite, the entire pass was drilled, blasted and cleared by hand. Hammer-Tap…Hammer-Tap… Blast!... Clear! Hammer-Tap…Hammer-Tap… Blast!... Clear!

Bill Haskell believed Hellfire Pass:

"…would be probably the most difficult section of the whole of the railway. And it had to be put through under pressure, and what they called the Speedo period, where the monsoons just lashed, and it rained for something like 140 days. It just cascaded down; And those poor blighters, they worked there in all those wretched conditions. Which is bad enough in themselves, but they were plagued with every tropical disease you could think of, and they were starved, and that’s not the finish of it – they had taskmasters who stood over them and belted them and hit them, there was just about everything you can run across that mitigated against them doing the job, but they just did and they had to do it, but at a terrible cost."

This section of the railway was one of the most deadly along the entire line. Work was divided into three groups. The first group exposed the rock; the hammer and tap men came next.

Ray Parkin wrote a book about his time in the railway cuttings. He called it Into the Smother. He described the rhythm of the hammer as almost “somnolent”, explaining:

“You stand in the same place all the time, balanced between both feet on uneven rocks. You strike squarely on the head of the steel drill. Clink! Clink! Clink! – squarely, or you bone-jar your mate’s hands as he holds the drill, lifting and turning with each strike you make.”

Once the drill bit reached one metre in depth, the gelignite charges could be set. This happened twice each shift.

Bill Dunn explains:

"You put the explosives in, and one person would be given a cigarette and he’d go round and light all the fuses. It was very important that you counted the fuses and counted the explosions, so you wouldn’t go back until the last explosion had happened off the number of fuses lit. That was very important."

As the explosives were detonated, everyone took cover so as not to be hit by the flying debris. Once the ground settled, the third group, the rock rollers, moved in on bare feet to carry away the sharp-edged rubble.

Just a few weeks after work on the Konyu cutting began, the monsoon rains came. It rained… and rained… and rained… and rained. Never letting up. Day after day, after day.

All the while, more Australian, British, Dutch, Indonesian and some American prisoners arrived. The Dutch, Indonesians and Americans came from Java. The Australians and Britons came from Singapore, as well as Java. For days the prisoners of war were forced to march through treacherous jungle to work camps at hastily demarcated points. Hellfire Pass was just another site of desolation along the way.

As the cutting got deeper, the engineers brought in iron wagons to dispose of the blasted rock. We can see one over there, just across the way. Prisoners were ordered to fill these skips to overflowing. The load would gather speed as it was pushed along mini rails to be dumped over the hill. Laurie West recalls:

"We were told that on one occasion, one of the Englishman I think – collapsed at the edge of the slope where they put all the rocks down, and the wagon was brought to the edge, and the men refused to tip it. And the Japanese were saying, you tip, you tip, so he got on to that and he tipped it himself, and buried the chap in the rocks, that’s what I heard. But whether it’s a true story or not, I don’t know, but it’s quite possible, they would have done a thing like that. Because life meant nothing to them."

The rail-laying team was advancing quicker than the pass was being cut. In February 1943 the Japanese brought the scheduled completion date forward. The pressure was on, and work on the railway entered its bleakest time – the Speedo period. As Sir John Carrick explains:

"The basis of speedo was of course that it was imperative that they get that last bit done as fast as possible, because the people in Burma were lacking all kinds of supplies – food and ammunition and everything else. So they did an imperative crash course, not concerned about who they slaughtered, and they brought more and more people."

All along the railway engineers pushed the disease-ridden men harder and longer. They were now working two 12 hour shifts. Day and night.

Tom Uren, describes the ordeal:

"…we would have to walk about six kilometers to and from, six kilometers to the railway, and then about six kilometers coming back. And in the wet season of course, when you’re going downhill in the muddy, slippery lane, your feet would go from underneath you, and you’d fall on the path, and you’d shake every bone in your body. We had no shoes. Sometimes you’d try to wrap something round your feet, hoping you could try to stop this skidding. Then there were places where you would be up to your knees in mud. And you got kind of trench feet – you know the trench feet the soldiers got during the first world war – well our feet were going like that too.

I was on the hammer and tap, but those that had to clear the rocks away, and the debris away, they would work from 16 to 20 hours a day, when you have to, particularly in the wet season getting to and from work, it was really a real hell for anybody. But the sick people, and you think of them and the way they, the hell they went through, that’s what stays with me."

On the 16th of October 1943, 15 months after work first begun, both ends of the Burma-Thailand Railway were joined at Kointaka – not far from the Three Pagodas Pass. With much pomp and a fair amount of ceremony, a well-fed Japanese soldier drove the final spike into a sleeper. The finished railway wound around 415 kilometers of jungle track, and included 688 steel and timber bridges. The cost in human life was savage. It’s estimated that approximately 12,800 Allied prisoners of war and up to 90,000 Asian labourers died working on the railway.

Death was a part of daily existence. The men who were still standing were given a fresh burst of hope that a train would carry them out of there alive. Bodies that were entirely depleted maintained a spirit that doggedly refused to die. Dr Rowley Richards explains:

"Probably the most important thing keeping us alive, for survival, was hope, maintaining hope. A common saying was, we’ll be home for Christmas, for Grandma’s birthday, for Easter, or Anzac Day, and we’d go from day to day and day. And to maintain that hope, we were able to defer disappointment by this particular manoeuvre, or disappointment was deferred."

Everyone had something or someone special to get back home to. John Varley remembers the carry-on of an officer he shared a hut with:

"He used to drive us mad – his wife was called Jeannie, and he used to go round from daylight till dark “I dream of Jeannie with the light brown hair…” or something. And we used to get so sick of this bloke singing Jeannie, but he was looking forward to getting home to Jeannie sort of thing. I can remember him very plainly, McBain was his name."

By September 1943 the Japanese were allowing the very sick to be taken to base hospitals. Some were even too ill to make that journey. And in December 1943 the prisoners of war were being shipped back to Singapore.

“Leaving is hard to believe” wrote Ray Parkin. “Many of our men are here in this valley of the Kwai Noi, through which the Railway now runs. They died when this parched, leafless forest was a dripping green cave with a black, muddy floor which seemed to suck men down like quicksand and hold them there until they could not rise again.

“The cemeteries in which we put the remains of these men are cleared and neat now. We worked hard to give them that order and a calm, deathlike dignity which was not available when the men died. When the next Wet Season comes the jungle will climb the fence again on to the graves, and hide this sorry little patch forever. Perhaps a bright red flower will bloom and a bird will drink its honey.”

In 1945, less than two years after the Railway was completed, the Allies began bombing raids. They targeted the bigger bridges rendering the railroad useless.

After the Japanese surrendered, the Thai government took over the deteriorated railway line but decided to only service it as far as Namtok. Rails along the remainder of the track were torn up, used for scrap, or merely rotted away in the jungle.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission war cemeteries in Kanchanaburi and Chungkai in Thailand and Thanbyuzayat in Burma now hold the remains of many of the prisoners of war who were buried in solitary graves or camp cemeteries.

I’ve travelled down some lonely roads

Both crooked tracks and straight

An’ I’ve learned life’s noblest creed

Summed up in one word, “Mate”

I’m thinking back across the years,

(A thing I do of late)

An’ this word sticks between my ears

You’ve got to have a mate.

Someone who’ll take you as you are

Regardless of your state

An’ Stand as firm as Ayers Rock

Because ‘e is your mate.

Me mind goes back to 43,

To slavery and ‘ate,

When man’s one chance to stay alive

Depended on ‘is mate.

With bamboo for a billie-can

An’ bamboo for a plate,

A bamboo paradise for bugs,

Was bed for me and me mate.

You’d slip and slither through the mud

An’ curse your rotten fate

But then you’d hear a quiet word:

“Don’t drop your bundle mate.”

An’ though it’s all so long ago

This truth I ‘ave to state:

A man don’t know what lonely means,

Til ‘e has lost his mate.

And so to all who ask us why

We keep these special dates

Like Anzac Day, I answer: “Why?”

“We’re thinking of our mates.”

An’ when I’ve left the drivers seat

An handed in my plates,

I’ll tell old Peter at the door:

“I’ve come to join me MATES.”

Literatura.

Biran MacArthur - "Surviving The Sword", wydawnictwo Abacus, 2007 r.

Eric Lomax - "The Railway Man", wydawnictwo Vintage, 1997 r.

Gavan McCormack, Hank Nelson - "The Burma-Thailand Railway", wydawnictwo Allen & Unwin Pty Ltd, 1993 r.

Warto oglądnąć.

1. Zwiedzając "Hellfire Pass" i inne miejsca na szlaku linii kolejowej.

2. The Burma railway.

Część 1.

Część 2.

Część 3.

Część 4.

Część 5.

Część 6.

5. War Stories - The Death Railway Survivor.

6. Fragment filmu nakręconego tuż powojnie. Przedstawia żołnierzy alianckich badających linię kolejową Birma-Tajlandia.

Filmy.

Filmy poruszające temat linii kolejowej Birma-Tajlandia.

1. "Most Na Rzece Kwai" (oryginalny tytuł "The Bridge On The River Kwai") - film wojenny.

2. "Powrót znad rzeki Kwai" (oryginalny tytuł "Return from the River Kwai") - film wojenny.

3. "Droga Do Wolności" (oryginalny tytuł "To End All Wars") - film wojenny.

4. "Jeńcy znad rzeki Kwai" (oryginalny tytuł "Kwai") - film dokumentalny.

Strona: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19